“Ornament” is an inadequate word to describe a metal gate we installed in our garden last year. And it is extraordinary because of the rich associations the gate has with the life that my wife Mary and I have shared since 1976. Every time we open this black metal gate or see it even from a distance, a whole range of memories and emotions stirs in us. And that’s what garden objects with depth of meaning should do: stir memories, remind us of associations, carry us back into previous experiences. Sometimes we buy objects; most of the time we create them.

The idea of giving Mary a gate for her garden originated with Mary’s fellow teachers upon her retirement. She had taught in the extraordinary two-room schoolhouse here in our hamlet of Westminster West for twenty-four years. Knowing that she was one serious gardener, they contacted Jon Taylor, a metal fabricator and artist who lives two miles or so from the school, and whose son Otis Mary had taught in the 3rd and 4th grades. The four teachers asked Jon to work with Mary to design a garden gate. He would then fabricate and install it as the embodiment of twenty-four years of Mary’s rich professional life, one that linked her deeply to the children and parents of our community of 800.

Now this is no ordinary stonewall. While Mary and I designed where it would go, the extraordinary dry-stone waller Dan Snow, with whom I had collaborated for years on many of our client’s gardens, built the wall itself.

Photo © Gordon Hayward

And he built it with disused stone that Mary’s fellow teacher for seventeen years, Claire Oglesby, had sold us from her property just over the west ridge from our place before moving to Brattleboro. The Derrig Boys, excavators from Putney with whom I had also worked for two decades or more in my design-build business, scooped up this long neglected wall stone. They delivered eight 7-yard dumptruck loads to our garden. Even the stone in the wall, then, resonated with the past to a time when the early settlers in the area were clearing land for farming.

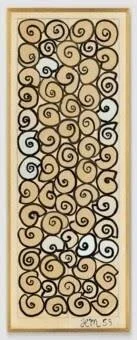

Another layer of memory that drove the design of the gate came from a few-day’s trip Mary and I made to Amsterdam in March, 2015. While there, we visited the Stedilijk Museum where a retrospective of Matisse’s work titled The Oasis of Matisse was up. The Stedilijk owned around 100 works by Matisse. Their collection was at the heart of the exhibit, around which the curators gathered works from across Europe by Vlaminck, Chagall, Van Gogh, Cezanne, Picasso, Maillol and Kirchner to establish the larger context in which Matisse was painting. After seeing this extraordinary show, we stopped in the bookstore and bought a copy of Henri Matisse: Drawing with Scissors – Masterpieces of The Late Years.

As we were casting about for design ideas for our new gate, we remembered one designed by Matisse pictured in this book. There on page 73 was a simple sketch dating from 1953 with this caption: “Henri Matisse: Design for the proposed ironwork grille door for the Albert D. Lasker mausoleum, ink on paper 273.1x109 cm, private collection.” The gate was never fabricated but the drawing Matisse did for the Lasker family remains. We showed Jon Taylor this sketch, took measurements of the gap in the stone wall where we wanted it installed, and Jon went off to develop sketches.

A few weeks later, Jon Taylor arrived with the gate. To say that it is substantial is an understatement. This stout yet delicate iron gate weighs fifty pounds or more, but it’s the grace it expresses that draws people to it, grace that is inspired by Matisse. It has a metal latch that makes a satisfying metallic clunk when falling into place. And it is anchored into a stone that Dan Snow had delivered as a wall-end stone years ago.

But there was one last association that we had not foreseen that made the gate all the more extraordinary. Jon had a collection of rusted steel hoops around ¾” in diameter that a Vermont farmer had given him from his abandoned silo. Decades ago, well back into the 19th Century, farmers built perhaps 16’ diameter, 24’ high wooden silos. They then installed these stout metal hoops perhaps ¾” in diameter around them every four to six feet up to the top of the silo to stabilize the structure. Clamps were affixed to the ends of these metal hoops to draw the hoops tight.

Photo © Gordon Hayward

As Jon was telling us about the metal he had used to make the Matisse- inspired spirals, Mary and I realized we were not 25’ from our pool garden. Three decades earlier we had installed a shallow pool in the saucer-shaped place that was the base of an abandoned silo that the Ranney family had built, probably in the early 1800’s. That wooden silo would have been stabilized by the very same stout metal hoops of the type from which Jon had built our gate.

When visitors to our garden see this gate, can they see all these facets of its story? No, they can’t. Only Mary and I know the full story. But what visitors do see is a lyrical gate, a beautiful, even playful gate made by an artist. And if they ask after the story of the gate, we’ll share it with them.