We gardeners can all look back to those adults in our childhood who inspired us to garden: an uncle, a mother, grandmother or aunt, a neighbor. We can all look back to models who had ways of relating to the natural world that remain in us today. And memories of them, sometimes startling, clear memories stretching over decades, attest to the lasting power of people from our pasts who remain very much alive through and in our gardens today.

Bill Andrus, a hermit by all definitions, was such a man for me. I grew up on an orchard 20 miles west of Hartford, Connecticut in the 1950’s and ‘60s. My parents, my two brothers and I tended the 14 acres of peach, apple and pear trees our father had planted in the early 1930’s. Every growing season we also looked after a very large vegetable garden for the house and four rows of asparagus over 100’ long, the spears of which we sold to customers who drove to the farm.

Because Bill, in his early 70’s in the 1950’s, was so very skillful with a scythe, my father hired him twice a year to help me and my father mow the grass along the stone walls and under the 14 acres of fruit trees that the sickle bar mower couldn’t reach. Dad and I would sharpen our scythes with a sharpening stone. Bill would sharpen his by pounding a little anvil that he carried in his back pocket into a cut off tree stump. Then, using a ball-peen hammer, he would sharpen his blade by striking the cutting edge of the blade against the little anvil. Bill’s swaths of hay were always the neatest, most regular of the three of us because his blade was so sharp, his swing perfection.

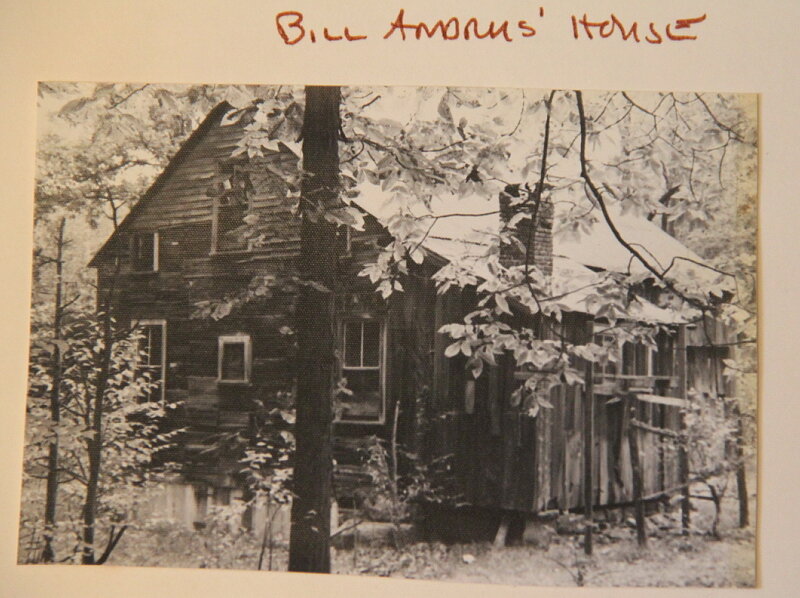

Bill, then in his late 60’s and single, lived about a mile through the woods from our farm on a pristine three acres he had cleared by hand out of woodland. It was an oases within his 20 acres and was in turn adjacent to thousands of acres of untouched watershed woodland for the city of Hartford. In the late 30’s, and single, he had sold 55 acres with house and barn that he had inherited from his late parents while retaining ownership of 20 or so acres of woodland. Sometime in the early 1940’s, he moved a 24’x36’ barn from what had been his family’s farm onto this 20 acre wooded parcel. He fashioned a room in the barn where he would live out the remaining 25 years of his life alone.

My brother John and I visited Bill maybe four or five times a year, and would often sit with him in a long, narrow room with a bed, a pot-bellied stove, a table, two chairs and a sink. His living space comprised one-eighth of the barn; the remaining 7/8th’s was for firewood, arrayed around the inside perimeter of the 1 ½ story barn. He stored his firewood in 6’ high stacks in seven gradations, from tiny kindling and small broken branches up to firewood size for his small stove. It was a marvel to behold.

For two or three years, my brother John, starting at around age ten or eleven, and I 2 ½ years older, walked a mile or so from our orchards and through the open woods to visit Bill. We always took back issues of Life Magazine for him for him to read. And the woods we walked through were mature, not the dense young woods of today with their thickets of understory brush. Widely spaced mature ash and oak, beech, hemlock and birch, and an occasional Tulip Poplar grew well apart from one another so we could see deep into the woods.

And then, as if by a kind of miracle, the woods and the path we walked through gave way to Bill’s three-acre clearing carpeted with hair-cap moss and grasses out of which rose a few grand Red Oaks dotted here and there. Bill’s barn was off to one side of this clearing. In the sunniest part was his always perfectly tended vegetable garden. And there were the raspberry, blueberry, gooseberry, asparagus and rhubarb patches, two or three peach, apple and plum trees and, of course, a well with rope and bucket and no electricity.

Off to one side of the clearing was a small workshop where he fashioned tool handles, bowls and plates, and a stool. I have, here in my office today, a coat hanger he gave me made from a tree branch with two small crooks in it for hanging light clothing. Between that workshop and his house/barn was a 5’-6’ high, 18’ long granite boulder that eons ago had split in such a way that there was a 2’ wide gap in the boulder. When going from the barn to his work shed, Bill walked between the two halves of this massive stone.

When we visited, Bill invariably took us into the woods to show us what was new: a squirrel had built a nest up that oak tree; a crow had taken up residence over there; seeing deer hoof-prints on the dirt path we were walking, he pointed out where a doe and fawn had passed through overnight. Now and again we were startled by a loud whirr when a partridge burst from a hiding place not all that far ahead of us. Squirrels would scold us from high in the trees.

What most impressed me about Bill and the place he had made for himself in the woods was his abiding respect and regard for the natural world. The fruit trees were well pruned; the vegetable garden abundant, with not a weed in sight. He kept the grass in those three acres low, almost lawn-like. It was all a model of how a man could live alone in such close communion with the natural world. I believe his connection to the outside world was limited to periodic visits a few times a year from the Goodwin family, descendants on his mother’s side, with flour, sugar, salt….

It’s easy to romanticize Bill’s life. There were parts of it that were no picnic. The last time my brother and I, sometime in the late 1950’s, visited Bill, we knew he was suffering from a facial skin ailment. He’d been unable to shave for a few years and so wore a white-gray beard down to his belt. As we approached the door you see in the attached photo, we could see the pull-down curtain over the entire door window was drawn. As we got closer, we could see his fingertips holding the curtain in place. He was just there on the other side of the door, but did not answer our knocking on it. We put the Life Magazines on the stone step and headed home. Bill died aged 83 in 1968.